Expert: ”The children are schooled in the ideals of the Third Reich”

Sturmvogel’s summer camp in southern Sweden is an indoctrination camp where children are drilled in military discipline and are schooled in nazi ideology, according to the award-winning German journalist and expert on German nazism, Andrea Röpke.

Uppdaterad: 2018-04-17, 19:53

Publicerad: 2016-07-30, 11:13

Lästid: 5 minuter

Du läser just nu gratis innehåll

Ditt stöd hjälper oss bekämpa rasism och främja demokrati genom granskning och kunskapsspridning.

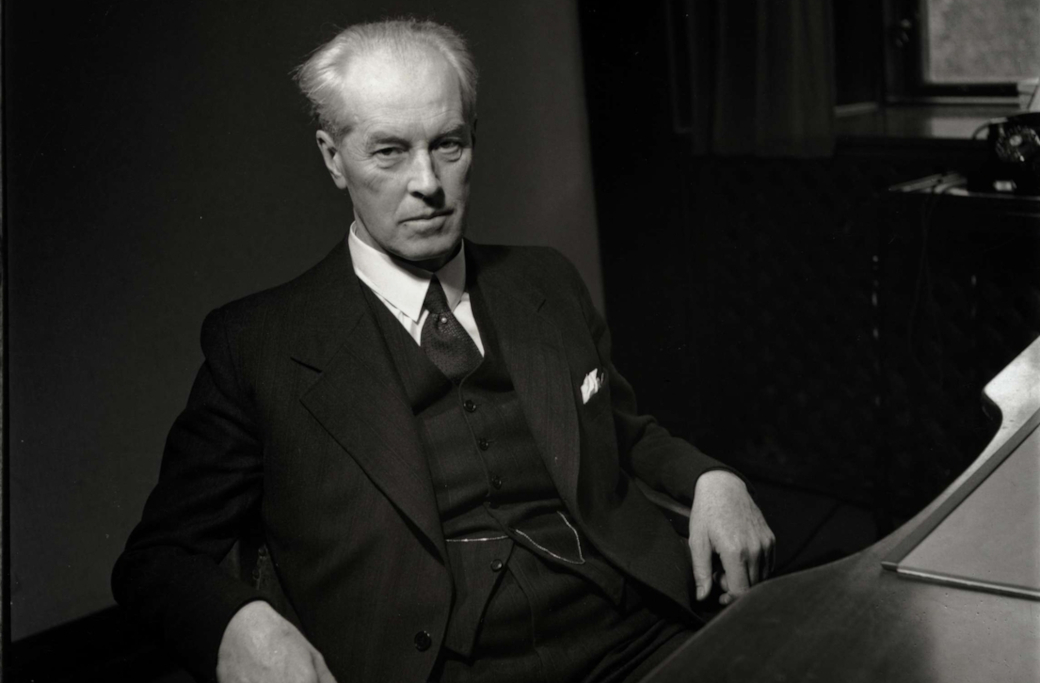

About Andrea Röpke

- Andrea Röpke is an academic and journalist focusing on right-wing extremism in Germany. She has won numerous awards in journalism, including the Otto Brenner Award in 2008, and in 2011 she was named Journalist of the Year by the trade publication Medium Magazin. In 2015 she received the Paul Spiegel Prize for Civic Courage from the Central Council of Jews in Germany. She has written several books about German nazism and was called as an expert witness in the trial against the German nazi terror cell, NSU.

"These secret nazi tent camps, which Sturmvogel now organizes regularly, are highly dangerous, because the children there are given a harsh ideological and military-inspired far-right upbringing. Bonding takes place and relationships form at these camps and in this way, parallel far-right societies have developed over the course of decades."

That is the view of Andrea Röpke, perhaps the foremost expert on the organized nazi child-rearing that is being carried out in Germany. She writes for the antifascist publication Der Rechte Rand and regularly contributes to the website Blick nach rechts, www.bnr.de.

The purpose of the camps is to remove the children, during the summer holidays, from the hated democratic society and instead let them experience a homogenous "Volksgemeinschaft" (folk-community) where there are no foreigners, "weak people" or political opponents. The children will be instilled with the ideals of the Third Reich, racist ideas and an elitist mentality. The children are to be brought up as new little Führers, who in turn are expected to raise the next generation in the same way.

In summary, "it is indeed very, very dangerous," says Andrea Röpke.

But the fact that Sturmvogel has assumed the leading role as fosterer of nationalist youth – after the banning in Germany of the organizations Wiking Jugend and HDJ –is something that officials of the German Constitutional Protection, the country's state security service, have missed. There was cheering after HDJ was banned in 2009, after antifascists using video footage had exposed the movement in a TV special. But after that not much has happened.

The security police does not monitor this movement; nor does it sound the alarm about its antidemocratic activities. Since Andrea Röpke wrote in Antifascistisches Infoblatt about a summer camp in 2015 in Grabow, Brandenburg, the regional Constitutional Protection office announced they would inspect that activity. That has been the only reaction so far, and no decision has yet been reached.

There are other far-right organizations that target children. But Sturmvogel today appears, says Andrea Röpke, to be the largest. Because it keeps such a low profile, not much is known about it. Most of the children appear to come from nationalist settler families, many of them living in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania but also in Bavaria, Hessen and Lower Saxony.

They start families – and in some cases almost colonies – of likeminded people, in order to raise their children in accordance with the principles of an elitist "Volksgemeinschaft". In Germany, the movement is called Völkisch.

The bringing-up of children does not only take place at the camps, of course, but also in the families and in the settler colonies. By an early age, the children are already noticeably different from their peers at school, as they are not allowed the same upbringing as other children. It is the family and the political group that set the norms and values; obedience and compliance with authority are the cardinal virtues. The children look old-fashioned – the girls are only ever seen wearing long dark skirts at the camps.

In many cases the grandparents of the children were members of the original Nazi party, and many parents are oriented towards the NPD. Today, some parents are also interested in the right-wing populist party AfD. The Sturmvogel youth camps are just one of the organization's activities.

"Traditional German folk-fests" for all ages are also organized. Both men and women wear traditional clothes; the nationalist overtones are strong. For example, on Walpurgis Night (April 30) this year, a May Dance was organized on the Lüneburg Heath in northern Germany.

This was a "Brauchtumszeremoni", meaning a party to keep old traditions alive. Some 200 guests from all over Germany took part, all in traditional dress; no women wore trousers or had short hair, for example. The dancing continued throughout the night. Many of the guests are active in Sturmvogel. This is a region where many far-right families have settled.

Entrepreneurs, craftsmen, teachers and physiotherapists – the women are usually housewives. Men and women spend their free time separate from each other.

Such May Dances and similar parties should be considered neo-nazi activities whose function is to maintain community coherence and forge a "brown" nationalist alternative culture. Andrea Röpke describes in an article how the regional NPD boss, Stefan Köster, stiffly joined a ring dance, while the party monitor Martin Götze greeted guests. The NPD, however, wasn't the only political party at the feast. At least two of the guests were representatives of AfD. One of them was Sascha Jung, who at a Munich rally this January threatened to beat counter-demonstrators with a folded-up German flag.

Translation: Morgan Finnsiö