German far-right children’s camp in Sweden

The school-age children are drilled for a week. Wearing uniform-style outfits and sporting traditional hairstyles, they take part in flag ceremonies, physical exercise and other activities at a remote location in the forested Småland province. Expo and Kvällsposten have documented the German organization ”Sturmvogel” and their camp week in Sweden.

Uppdaterad: 2018-04-17, 19:53

Publicerad: 2016-07-30, 08:52

Lästid: 7 minuter

Du läser just nu gratis innehåll

Ditt stöd hjälper oss bekämpa rasism och främja demokrati genom granskning och kunskapsspridning.

The red-and-white banner is blazoned with a black bird of prey. Beneath the banner children stand at attention, all of them blond with traditional hairstyles, wearing uniform-style outfits bearing the red-white-black symbol.

At a given signal, they line up, salute the flag and sing.

It is the end of July, 2016, and German right-wing extremists are organizing a children's camp in the south of Sweden. For a full week, small children – some of them barely of school age – are drilled by instructors at a remote location in the woods of Småland.

Expo and Kvällsposten have documented the German organization "Sturmvogel" and its camp week in Sweden.

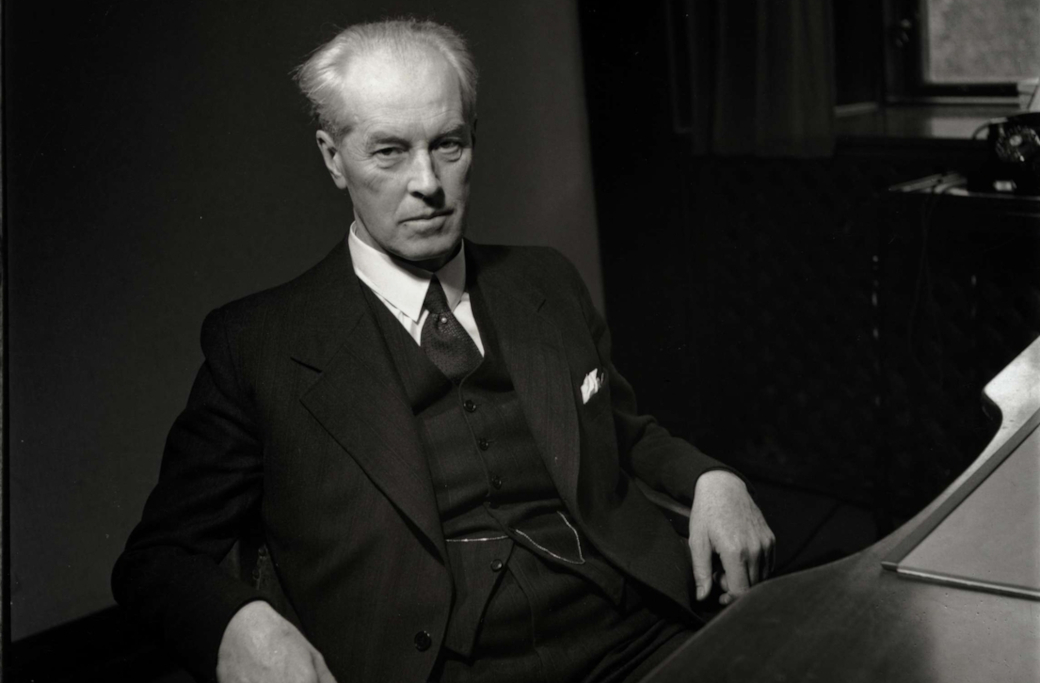

It is just after 7 a.m. in the Småland woods, many miles away from the nearest major town. Children's voices are heard, and after a minute or two a group passes by us closely – some fifteen children, the oldest of them around 15-16 years old, the youngest ones barely old enough for school. All of them boys, all of them dressed the same way – shorts and white undershirts. They run in a line, the older youths spread out along the column. On the other side of the road there are two large plots of land with a number of buildings. Documents show that these properties are linked, through a phone subscription and through previous owners, to a married German couple – the husband in his nineties – who as of decades are well-documented leading figures in German nazism and the far-right.

The current owner is a person with the same surname as the previous owners, who in turn still have a telephone in one of the properties. In the yard next to the main building, several German-registered vehicles are parked. A bit further into the long and narrow land plot, which continues on into the forest and obscurity, more vehicles are parked. Here, further in, the group has made camp: tents, washing lines, water containers and spaces for meals fill the clearing.

Just before 8 a.m. there is great activity. As the time nears 8.30, all goes quiet. It is time for the morning muster, and through the trees we can see the red-white-black banner being raised. A few loud cries. Then silence once more. Suddenly, all that is heard is a chorus of children's voices – the morning muster begins with a traditional German folk song.

The banner, blazoned with the silhouette of a bird of prey, belongs to the German organization "Sturmvogel" – Storm Bird. German experts describe Sturmvogel as a German nationalist youth organization with deep roots in nazism and Holocaust denial. The organisation was set up in 1987 and has personal ties to the organizations Wiking Jugend and Heimattreue Deutsche Jugend, HBJ, both of which are now banned in Germany.

At previous camps in Germany, children have participated whose parents have denied the Holocaust, a crime under German law, such as the Swiss citizen Bernhard Schaub, a known and convicted Holocaust denier.

For many years, the group has kept an extremely low profile, and by attracting no attention, not carrying out demonstrations or rallies and never giving interviews, they have succeeded in staying below the radar – not least that of the German Constitutional Protection, which prohibits nazi organisations. In order to find event spaces and locations in Germany for their recurring summer and winter camps, the group has presented itself as an ordinary Scout group. Now a week-long camp is being held in Sweden, in a remote area in the south-west of Småland province.

"The most important explanation is that they are trying to hide in order to avoid attention from the security police. Other similar organizations have previously been banned, and Sturmvogel wants to avoid that," says Andrea Röpke, a German journalist and expert on far-right child and youth groups in Germany.

A few days earlier, the group arrived in Trelleborg, having taken a ferry from Germany. They continued by train to a village in Småland, where the group was met up by several cars with German license plates. The journey's destination, the remote plot of land in the woods, requires further travel. When Kvällsposten returns to the plot a few days later, the group has established its tent camp.

On the yard, the German-registered cars that transported the group on its last leg of the journey are parked. The group finishes its morning gathering, a so called Appell (roll call). The muster is highly strict – according to German experts, the children are not allowed to move or speak. In cases from Germany, there are photos of children collapsing during the roll call.

After the muster, the group moves towards a large, round tent that has been raised further down the plot. Chatter and laughter can be heard, and then suddenly an adult's voice: "Alles Aus!" – "Silence!" A few minutes later, breakfast is finished. Soon the camp is full of activity again.

The program at Sturmvogel's camp often follows the same routine: the morning flag ceremony is followed by physical activity, musters and different kinds of work.

Discipline is severe. Clothes and hairstyles are traditional: green uniform shirts with symbols; long skirts and pigtails for girls. Non-German words are to be avoided. According to German experts, the movement is largely a family affair. Often, participating families have been nazis for several generations. Traditions from the Third Reich have survived.

"The nationalist fostering of youth is very important to them, and the camps are an important part of that activity," says Andrea Röpke.

Since the 19th century, there has existed in Germany a so-called Völkisch movement, which was embraced by nazism. Today the movement appears in a new form by celebrating traditional life and renouncing modernity. Romanticism of nature, outdoor activiy and tradition are the leading lights.

Just before lunch, smaller groups of participants have ventured out into the surrounding area. In a deforested clearing, a group of ten-year-old boys gather branches. A little further away, a couple of girls in their early teens pick blueberries.

Suddenly a trumpet signal rings out, and some of the 30-40 campers run through the forest to yet another muster under the red-white-black banner.

Landowners deny the existence of the camp

When the persons living on the property, a man and a woman, are confronted, they deny that Sturmvogel is on their land.

"They are grandchildren and friends," the woman in the house tells Kvällsposten's reporters.

A younger man explains that he does not feel like being in the newspapers, and rejects any information about a Sturmvogel camp.

"It's about nature. It is for grandchildren with friends."

When we ask if he is the leader of the group, he says no and points to the woman.

"No, it is my mother," he says and gestures to the woman who seems to live in the house.

The reporters are not allowed to speak with the camp leader.

They do not wish to give heir names, and maintain that they have nothing to do with Sturmvogel.

Translation: Morgan Finnsiö